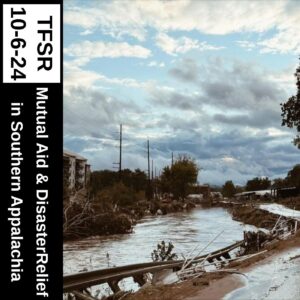

Mutual Aid and Disaster Relief in Southern Appalachia

Over the first weekend of October, 2024, there was a deluge from two storms (including level 4 Hurricane Helene) descended on southern Appalachia, mostly on the eastern side which includes Asheville and other parts of western NC, eastern TN, south eastern Ohio, and northern Georgia. At the point of this recording there are over 200 known dead and hundreds missing, portions of the region continue to be without electricity or cellular service, and where the toxic mud and water linger and separate people from medical and community care. This episode, we’re speaking with two people who’ve lived in the region and have been helping other residents distribute storm relief.

Over the first weekend of October, 2024, there was a deluge from two storms (including level 4 Hurricane Helene) descended on southern Appalachia, mostly on the eastern side which includes Asheville and other parts of western NC, eastern TN, south eastern Ohio, and northern Georgia. At the point of this recording there are over 200 known dead and hundreds missing, portions of the region continue to be without electricity or cellular service, and where the toxic mud and water linger and separate people from medical and community care. This episode, we’re speaking with two people who’ve lived in the region and have been helping other residents distribute storm relief.

- Transcripts

- PDF (Unimposed)

- Zine (Imposed PDF)

Groups worth following doing work on the ground include:

- Mutual Aid Disaster Relief

- Appalachian Medical Solidarity

- Hood Huggers

- Rural Organizing And Resilience

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- 500 Year Flood by Adam Pope

- Day 3 on Pigeon River by Sarah Howell

. … . ..

Chris Transcrip

Chris: Hey, call me Chris. He and they pronouns, and I’m in Asheville, North Carolina. I do street medical work- both grassroots and I have a medical job that has me on the street as well.

TFSR: I wonder if you could talk about your experience, both as a resident of western North Carolina and also, as a medical professional and medic/activist, around what the storm was like for you. How’s it’s been?

Chris: Well, it was looking like a serious storm. I was at work Thursday, and made sure to do a couple of smart things like filling up the gas tank and thinking about preparations. Then Friday morning, hearing the news, we knew it was going to be pretty bad before I went to work. Then it was just really slammed. A lot of people were caught off guard by the severity. I think pretty much everybody was caught off guard. Unfortunately, the extra shelters that did get set up the night before had to be closed because it was in a flood plain, essentially on the banks of the Swannanoa River, so it had to be emergently evacuated. That extra shelter is on the grounds of the veterans homeless shelter, specifically male veterans. It was all emergency evacuated in the middle of the night, and many of the veterans are older, are in wheelchairs or have walkers. Everyone got out in that case, and the building was definitely inundated later. So this leads into the morning, because all those folks went to the Civic Center here in Asheville.

Everywhere had power down. The other shelter I mentioned was in West Asheville, and it lost power. They moved everybody out of there as well. It wasn’t flooded, though. So then the Civic Center became a shelter, but there were many problems. When I came in to work, it was already very severe wind and rain. I went downtown, and within the first hour, everyone, all the workers, were ordered to finish what they’re doing and go back to their home base and stay there for the time being because of severity. I was already in a building, a facility with homeless people with medical needs, a respite. So I stayed there, and then found out that somebody was let in the building, who was outside. They took shelter there and told us there were a bunch of folks gathered up at the day drop-in place a block away, and there was a crowd. They were just in the weather, because you know that place didn’t open with everything going on. So me and another co-worker met up and just went out in the weather and took everybody in two trips up to the Civic Center place where their people were sheltering in the worst of it. Me and my coworker got there. We were able to get there fast and were able to get them in the car and drive them up through debris coming across the road. In fact, on the second trip, I ran over something, and it punctured both tires on the passenger side. We made it up to the civic center, and then had to park the car that had two flat tires.

Then we were in the Civic Center. 100 plus [people] and people kept coming. The National Guard was bringing people in the big deuce and a half trucks. Especially later, when it died down a little bit and the worst was over, the city busses were coming with evacuees from all kinds of low lying places, various parts of the county. We didn’t have any power. We just had emergency lighting in the Civic Center. Five Civic Center staff and me and another co worker just set up an impromptu aid station, which was very reminiscent of all the street medic work I’ve done. I was doing the same thing that we’ve done, whether it was training camp or base camps for actions or mass mobilizations, all these different things over the years. We had to set one up at the Civic Center. Certainly people would come and ask us for help for different medical issues. Most of them were minor: headaches, little cuts. Had a couple people that needed to really be in a hospital, but we figured that out, just deal with what’s in front of us and keep our heads on, make a little space, hand write a sign that says medical and stay there, have somebody there, and have some supplies out of the vehicles, and then be there to talk to people. Go around and mingle and check in. That is a very important thing to do if people find themselves in that situation. Whatever your resources are, whoever you’re with, it has a huge psychological impact, and people did express that to us.

We ended up all leaving by nightfall. There was no way to get power to the Civic Center. That was a SNAFU that the State did not foresee because they didn’t look at it, but that’s a different topic.

The last little piece was, we did help to identify folks who had more acute chronic medical issues. They really needed more support. It wouldn’t be good for them to go to a general shelter with hundreds of people and hardly any medical support there. People were offered to go to a medical focused shelter instead of the general, big one at the agricultural center in the county. The last thing we did was help more medically fragile people get onto a different bus. The next couple days, we mostly supported that shelter.

TFSR: There’s a huge geographical elevation dip between that part of downtown on the side of the highway versus the hill that the hospitals are on that I imagine turned it into islands, almost.

Chris: Different hill, yeah. It was hard to navigate because, like I said, one person was having a pretty serious issue and they needed to go to the hospital. We just had to figure out a way to transport them over as soon as we could safely do it and navigate the trees, the debris, the power lines. I was in New Orleans right after Katrina. It’s the reason I decided to go on and further my training and involvement in disaster relief and the medical field. It definitely reminded me of that, because I had never been through such a storm directly. One of my memories from New Orleans was how even just traveling anywhere, you have to be really vigilant about how you do it, because there are so many hazards everywhere. If the vehicle becomes disabled, like ours did, then you’re there, you’re stuck. Or if you get injured, even a minor injury can become a much bigger problem because of situation. I was really glad to be on high ground, for sure, since we didn’t have to worry about the flood.

That civic center is fairly old, in civic center terms and I think that’s part of the reason when the local fire department brought a really big-ass generator on a trailer, that would have powered, the building (I don’t know how much those cost, probably 50 plus grand) they discovered that the plugs wouldn’t match because the amperage doesn’t match. The generator would generate 100 amps that building only takes 60. There are converters or reducers, but they didn’t have one. That’s the main reason that they sent us out from the Civic Center, because there would be no power. I don’t think there’s power over there now. I don’t know.

TFSR: How were facilities at the Ag Center?

Chris: There’s a big building at the Ag Center there that was being used for all the cots and all the sheltering. There’s a small kitchen in that building. It’s a big, open, tall building, kind of like a small arena but flat. It was not very good conditions when I was there, because it also didn’t have any power or water. They had a couple of small generators to try to power at least some people’s oxygen devices, which is an ongoing issue. All the people that are on oxygen; people might have tanks, but they don’t last super long. At one point I was actually there when they had a generator that they were able to use for a little bit but it was owned by a rental company somewhere nearby, and they actually came and took it back.

TFSR: They repossessed it in the middle of hurricane relief?

Chris: They took it back in front of everybody, in front of hundreds of people. It’s a private rental company. What do you think they’re going to use it for? To make money! I’m assuming. I don’t know for sure, but I think it’s a good bet. So that was that. After a little while, I finally found a couple other small generators. Now, there are national level resources there that are way better set up, as far as resources. The police are also much more reinforced there. I can only imagine a lot of people just wanted to leave once the weather died down and things are much more regimented, as they get when FEMA arrives. There’s a lot of people that I am working with a lot, who already live on the street. They’re very capable of survival in many ways, so they weathered the immediate storm. I’m going to see who’s out tomorrow when I go back to work. There definitely are resources flowing in. There’s a lot of things getting set up.

I haven’t been down to the Ag Center lately, but there’s a couple of shelters in the local community college. That’s where that medical focus shelter was set up. It was tough to get through the first couple of days there too. It’s a good idea to do that type of shelter. However, that’s where a bunch of people need oxygen machines, and you got two tiny generators. Awesome, but they need gas. So it’s a struggle. People need water. Some group came and threw down these sweet Port-A-John trailers. They’re ready to go. But there were like five steps get into each every one of them. They’re on a trailer, so almost nobody in the medical shelter could use them. Luckily, there was one Port-A-John that was at ground level. So that was another thing that had to be swapped. We had to get through the gap of the immediate, the most severe part. I forget all the names of the phases, but there’s phases of disaster. The immediate acute, when there’s rescues happening and people are having to scramble just for life. Then there’s the next part where all the damage is fresh, and people are still needing to get rescued. Most people are looking for shelter, water, basics. So we help a bunch of people get through that second stage, and now a lot of resources are pouring in both. There are three streams really. There’s governmental/official, there’s nonprofit, and there’s grassroots.

TFSR: This is the final straw radio, and you just heard our chat with Chris, an EMT doing care in western North Carolina.

I know that I am kind of avoidant to give donations, or promote donations for NGO’s or nonprofits, like official groups, in a lot of cases, because a lot of money from those organizations like Red Cross can go into administrative position funding or lobbying efforts, or other type things, and not actually get to the people that are directly needing the supplies or the resources on the ground. Which is not to say that they don’t do some stuff very well but, are there any good organizations that people might consider giving donations to that can be on the ground? What are good ways of determining if a group is trustworthy? Somebody brought up, for instance a group called Appalachian Medical Solidarity that has been raising funds and someone who was looking looking at their history was like, “Well, they don’t have much of a pattern on social media over the last five years. They’ve been off and on.”

Chris: My experience is that some groups are good on social media. I was actually just reminded of that group? Tell me if I’m wrong but was it Queer Appalachia?

TFSR: Yeah.

Chris: They had a really great, sweet social media presence, had sweet merch, were raising a lot of money for good causes, supposedly. People can look up the articles about how that went.

TFSR: There’s a big New York Times article about it that seemed to go into a lot of detail.

Chris: It’s true social media changes fairly rapidly. Even just platforms, pretty rapidly change. So people are looking at different things. It’s good to have some media presence in that sense, for a group. That’s related to something I was reminded of when you mentioned the Red Cross and all the administrative costs, which I do think are bloated. The Red Cross is so huge that it’s it’s essentially an arm of the of the government, of the State in a lot of ways. However they do last, chapters and their storage. They’re ready. They last through- between events, is what I’m getting at. It seems like it’s hard, because I’ve been involved in different ones, when there’s not a lot going on in the sense of urgency and crisis and street actions, to maintain infrastructure and maybe not build, but at least maintain structures of the grouping, the physical storage, all that stuff. Fundraising. I understand AMS is getting a lot of funds right now. So much that I think people are good to find other places because when a lot of money goes into one channel, it can become a bottleneck, it can be a technological problem too, or just capacity.

I can say who I would recommend. I know Mutual Aid Disaster Relief does have a track record of maintaining some of their systems, their fundraising. They are an official nonprofit, with very close ties with the grassroots. It’s essentially a grassroots organization that is an official nonprofit, that is has integrity, as far as I know. I’ve worked with them in different places and different instances. So I would recommend them. And there’s some other local places.

TFSR: Rural Organizing and Resilience would be one that we’ve interviewed before on the show. I don’t know what their online presence is, but ROAR does good work.

Chris: Right. They have a basic website, and they have a Facebook. They definitely have a fundraising place that people can send money to. I know I’ve been in touch with them. They’re rocking it in Madison County in particular, and some other of the more rural areas right near Asheville. I don’t know what their presence is on media, but they do have some fundraising channels. I know directly that folks have been bringing in supplies as well, spending the money, getting the supplies, bringing them back into the area.

TFSR: Maybe, if we think about disaster and access to resources in terms of marginalization- geographic or cultural or economic or whatever- a lot of the most affected people by the storm are the people that were already pre-existing in marginalized positions. Which is cool that Sumud is doing things, or members at least, are doing things. Another element too, with what we mentioned with ROAR, is that they work in rural areas that are often disconnected from resources and where a little change in the infrastructure can really cut someone off from access to fresh water, to electricity, to heat, to power, to medicine.

Chris: It’s really important for people to remember that we all have blind spots. So coming into an area- I think it’s a good principle to be invited and to not just necessarily show up. I get it if you don’t know who to talk to, but there are people on the ground already and it’s very heartening to me. I haven’t been through this before, directly, where I live. I’ve been to several disasters to plug in.

Since Friday, there’s a bunch going on already. I just drove into town, and just in my drive, I saw at least a half a dozen distribution sites at different places, like an elementary school, a fire department, a couple of churches. And restaurants that have food are just cooking it and giving it away. No one turned away. I think, going through covid, and other experiences too, a lot of people built up their their solidarity muscles, so to speak, and are ready to face the challenge in front of them and not wait for the state or the big nonprofits to start it up, get us through. Of course, most everybody’s relying on the reanimation of industrial society here- all the big systems, the hierarchical systems- to provide, again, sure. However, I think there’s progress. At least I feel like there is, just in my direct experience. Like thinking about people who are living more on the margins in general, every day, under capitalism and under different oppressive systems. There’s so much to learn. When somebody shares some knowledge with me at work, that helps my own survival too. I’m so grateful, and I always, I feel like we are in this together. I say that out loud to people. I don’t feel like it’s a fake thing. We’re here. I’m standing here next to you. Knowing that this is a long emergency, a disaster, (I think it’s the name of a book, actually A Long Emergency), but where we’re going, where the future is now, the disasters are happening everywhere.

Capitalism and the big systems are getting just less and less effective at providing what we actually need. This hospital here got bought out by the biggest hospital company in the country, and they’re so huge and rich, and the service became so much worse. Everybody saw it. Everybody sees it. There would it was a like a mini-disaster on random Tuesdays. EMS, workers, EMS, ambulances would have patients on their stretchers for two plus hours waiting, just line out the door into the parking lot just on a regular day, because the hospital is too damn cheap, and they wanted to break the union. They want to break the union still, that had just got established, by under-staffing and being cheap and all these things. Not to get on a tangent there, but that’s an example of things that we need to face. Yeah, this sucks, and it also is an opportunity to learn about people who are neighbors, to meet new people, work together, find ways to deal with this and remember those things and maintain some relationships. Yeah, long haul, right?

TFSR: I remember, out of the 2008 economic crisis that capitalism created, you got a huge infusion of people living on the streets because their housing was taken away from them. Similarly, after covid, doing mutual aid work in Asheville, where, like so many other places, the narrative is that people are being shipped in from out of town, they don’t they don’t belong here and they’re living on the streets and using our resources. For folks that are housing precarious or who are on the streets, every time there’s a crisis people get pushed out of their housing. Often they don’t have the resources to move to another city, and so most the homeless people that are in Asheville are people that have lived in Asheville for a long time. With all of the damage that was done by the storm, between people’s houses being washed away, roads being washed out, flood damage and mud everywhere, how do you think this is going to be impacting the homeless population in Asheville?

Chris: Well, I think people can look back to New Orleans for some clear lessons there. I think about a guy who I’ve seen and encountered in my work. He had just got housing like a week ago, and a big ass tree just went through his house while he was in it. He told me the story, and now he’s back on the street. Is that how it’s going to be? What’s going to happen to that house? It’s probably going to be fixed but the effort and money to fix it…who knows how long that take will take? Depending on who actually owns it, what would they do with it? Are they going to keep it in a program where people can get placed for housing? Good question. There’s a lot of damage in some of these rural places too. Outside of Asheville, it gets rural pretty quick and it’s hard to tell what’s going to be the future of those houses, those areas, those neighborhoods. From what I’ve seen in the past, people will rebuild on the same exact place where everything was destroyed, like in the Lower Ninth Ward, for example. What is it going to do for gentrification? I don’t know.

Disasters are at recurring faster and faster frequencies, severity. There’s a point where it counterbalances the things like gentrification. At some point it’s gonna be really hard. I’m thinking about the housing projects here. I literally met the CEO of a big retirement community, that also has some assisted living buildings. I’m pretty sure it has an actual skilled nursing facility in it. It’s a big place, really nice, high end and the CEO walked up to figure out how to make sure his people are going to be provided for. On the other hand, where’s the public housing? I don’t know everything that’s going on. I don’t know what the CEO of the housing authority here is doing necessarily. I know it’s true that people in those projects are not getting the same service. Who’s advocating for them to get that? The babies, elderly, families with very small children, infants even. We’re needing the diapers, the formula, the supplies. I know that grassroots people are delivering those now, so we got that.

TFSR: Yeah, as you said, blind spots. The best we can do is to try to reduce them and move forward. Well, Chris, thanks a lot for having this chat. Any other things you want to throw in? I’ve kept you on for longer than I said that I would.

Chris: I appreciate that people are getting involved. Like I said, we gotta check ourselves. We check our savior complex. There’s no heroes- that’s actually just a mechanism of manipulation. Having been in the military and other jobs where we’re called heroes, it’s just really to convince us to sacrifice ourselves. That’s something that separates us. We need to get past barriers, whether they’re social, institutional, so that we all can survive and also thrive. So I appreciate people getting ready. That’s my final thought. Let’s not just be adrenaline junkies okay? Let’s build and at least maintain it at a plateau, so that we don’t have to rebuild a bunch of it when the shit hits the fan again.

. … . ..

Chris Transkript auf Deutsch

(thanks to Sophie!)

Chris: Hey, nenn mich Chris. Er und sie pronomen, und ich bin in Asheville, North Carolina. Ich arbeite als Straßenmediziner, sowohl an der Basis, als auch als Arzt, der mich auch auf die Straße bringt.

TFSR: Ich frage mich, ob Du über Deine Erfahrungen als Einwohner von West-North Carolina und auch als Mediziner und Sanitäter/Aktivist darüber sprechen könnten, wie der Sturm für Dich war. Wie war es?

Chris: Nun, es sah nach einem schweren Sturm aus. Ich war am Donnerstag auf der Arbeit und habe darauf geachtet, ein paar kluge Dinge zu tun, wie den Tank aufzufüllen und über die Vorbereitungen nachzudenken. Als wir dann am Freitagmorgen die Nachrichten hörten, wussten wir, dass es ziemlich schlimm werden würde, bevor ich zur Arbeit ging. Dann wurde es richtig heftig. Viele Menschen waren von der Härte überrascht. Ich glaube, so ziemlich jeder war überrascht. Leider mussten die zusätzlichen Notunterkünfte, die in der Nacht zuvor errichtet worden waren, geschlossen werden, da sie sich in einem Überschwemmungsgebiet befanden, im Wesentlichen am Ufer des Swannanoa River, und daher dringend evakuiert werden mussten. Diese zusätzliche Unterkunft befindet sich auf dem Gelände des Obdachlosenheims für Veteranen, insbesondere für männliche Veteranen. Die Evakuierung erfolgte mitten in der Nacht und viele der Veteranen sind älter, sitzen im Rollstuhl oder haben Gehhilfen. In diesem Fall stiegen alle aus und das Gebäude wurde später definitiv überschwemmt. Das war also am Morgen, all diese Leute sind hier in Asheville zum Civic Center gegangen.

Überall war der Strom ausgefallen. Das andere Veterinärheim, das ich erwähnt habe, befand sich in West Asheville und hatte keinen Strom mehr. Sie haben auch dort alle rausgeholt. Allerdings war es nicht überschwemmt. Dann wurde das Bürgerzentrum zu einem Zufluchtsort, aber es gab viele Probleme. Als ich zur Arbeit kam, herrschte bereits sehr starker Wind und Regen. Ich ging in die Innenstadt, und innerhalb der ersten Stunde wurde allen Arbeitern, befohlen, ihre Arbeit zu beenden und zu ihrer Heimatbasis zurückzukehren und wegen der Schwere vorerst dort zu bleiben. Ich war bereits in einem Gebäude, einer Einrichtung für Obdachlose mit medizinischem Bedarf und einer Atempause. Also blieb ich dort und erfuhr dann, dass jemand in das Gebäude gelassen wurde, der draußen war. Sie suchten dort Schutz und erzählten uns, dass sich eine Menge Leute an der Tagesanlaufstelle einen Block entfernt versammelt hätten, und dass dort eine Menschenmenge war. Sie waren nur wegen des Wetters da, denn wie sie wissen, öffnete der Laden nicht, als es losging. Also trafen ich und ein anderer Kollege uns und gingen einfach bei schlechtem Wetter raus und nahmen alle auf zwei Fahrten mit zum Civic Center, wo ihre Leute in der schlimmsten Situation Zuflucht suchten. Mein Kollege und ich kamen dort an. Wir konnten schnell dort ankommen, sie ins Auto setzen und durch Trümmer, die auf der Straße aufkamen, hochfahren. Tatsächlich bin ich bei der zweiten Fahrt über etwas gefahren, und es hat beide Reifen auf der Beifahrerseite durchstochen. Wir schafften es bis zum Bürgerzentrum und mussten dann das Auto mit zwei platten Reifen parken.

Dann waren wir im Civic Center. Über 100 [Leute] und es kamen immer wieder Leute. Die Nationalgarde brachte Leute in großen zweieinhalb Lastwagen. Besonders später, als es etwas nachließ und das Schlimmste überstanden war, kamen die Stadtbusse mit Evakuierten aus allen möglichen tiefer gelegenen Orten und verschiedenen Teilen des Landkreises. Wir hatten keinen Strom. Wir hatten gerade Notbeleuchtung im Civic Center. Fünf Mitarbeiter des Bürgerzentrums und ich und ein weiterer Kollege haben gerade eine spontane Verpflegungsstation eingerichtet, die sehr an all die Straßensanitäterarbeit erinnert, die ich geleistet habe. Ich habe das Gleiche gemacht, ob es nun Trainingslager oder Basislager für Aktionen oder Massenmobilisierungen waren, all diese unterschiedlichen Dinge im Laufe der Jahre. Wir mussten eines im Bürgerzentrum aufstellen. Sicherlich würden Menschen kommen und uns um Hilfe bei verschiedenen medizinischen Problemen bitten. Die meisten davon waren geringfügig: Kopfschmerzen, kleine Schnittwunden. Es gab ein paar Leute, die wirklich ins Krankenhaus mussten, aber wir haben das herausgefunden: Einfach mit dem klarkommen, was vor uns liegt, und den Kopf behalten, etwas Platz schaffen, mit der Hand ein Schild mit der Aufschrift „Medizin“ schreiben und dort bleiben. Jemanden da haben, ein paar Vorräte aus den Fahrzeugen holen und dann da sein, um mit den Leuten zu reden. Gehen Sie herum, mischen Sie sich unter die Leute und melden Sie sich an. Das ist sehr wichtig, wenn sich Menschen in einer solchen Situation befinden. Was auch immer Ihre Ressourcen sind, mit wem Sie auch zusammen sind, es hat enorme psychologische Auswirkungen, und das haben uns die Leute auch zum Ausdruck gebracht.

Am Ende sind wir alle bei Einbruch der Dunkelheit abgereist. Es gab keine Möglichkeit, das Civic Center mit Strom zu versorgen. Das war ein SNAFU, den der Staat nicht vorhergesehen hat, weil er sich nicht damit befasst hat, aber das ist ein anderes Thema.

Der letzte kleine Beitrag war, dass wir dabei geholfen haben, Menschen zu identifizieren, die akutere chronische medizinische Probleme hatten. Sie brauchten wirklich mehr Unterstützung. Es wäre nicht gut für sie, mit Hunderten von Menschen und kaum medizinischer Versorgung in eine allgemeine Notunterkunft zu gehen. Den Menschen wurde angeboten, statt der allgemeinen, großen Unterkunft im Landwirtschaftszentrum des Kreises in eine medizinische Notunterkunft zu gehen. Das Letzte, was wir getan haben, war, gesundheitlich schwachen Menschen dabei zu helfen, in einen anderen Bus zu steigen. In den nächsten Tagen unterstützten wir hauptsächlich dieses Veterinärheim.

TFSR: Es gibt einen großen geografischen Höhenunterschied zwischen dem Teil der Innenstadt an der Seite der Autobahn und dem Hügel, auf dem sich die Krankenhäuser befinden, die der Hurricane meiner Meinung nach fast in Inseln verwandelt hat.

Chris: Anderer Hügel, ja. Es war schwierig, sich zurechtzufinden, da, wie gesagt, eine Person ein ziemlich ernstes Problem hatte und ins Krankenhaus musste. Wir mussten nur einen Weg finden, sie so schnell wie möglich dorthin zu transportieren und sicher durch die Bäume, den Schutt und die Stromleitungen zu navigieren. Ich war direkt nach Katrina in New Orleans. Aus diesem Grund habe ich beschlossen, meine Ausbildung und mein Engagement in der Katastrophenhilfe und im medizinischen Bereich fortzusetzen und weiterzuentwickeln. Daran hat es mich definitiv erinnert, denn so einen Sturm hatte ich noch nie direkt erlebt. Eine meiner Erinnerungen aus New Orleans war, dass man schon beim Reisen überall sehr vorsichtig sein muss, weil es überall so viele Gefahren gibt. Wenn das Fahrzeug kaputt geht, wie es bei uns der Fall war, dann stecken Sie fest. Oder wenn Sie sich verletzen, kann aufgrund der Situation selbst eine geringfügige Verletzung zu einem viel größeren Problem werden. Ich war wirklich froh, auf einer Anhöhe zu sein, da wir uns keine Sorgen wegen der Überschwemmung machen mussten.

Dieses Bürgerzentrum ist für Bürgerzentrumsbegriffe ziemlich alt, und ich denke, das ist einer der Gründe, warum die örtliche Feuerwehr einen wirklich großen Generator auf einem Anhänger mitgebracht hat, der das Gebäude mit Strom versorgt hätte (ich weiß nicht, wie viel). (die kosten wahrscheinlich mehr als 50 Riesen) Sie stellten fest, dass die Stecker nicht zusammenpassten, weil die Stromstärke nicht übereinstimmte. Der Generator würde 100 Ampere erzeugen, das Gebäude benötigt nur 60 Ampere. Es gibt Konverter oder Reduzierer, aber sie hatten keinen. Das ist der Hauptgrund dafür, dass sie uns aus dem Bürgerzentrum vertrieben haben, weil es dort keinen Strom geben würde. Ich glaube nicht, dass es dort derzeit Strom gibt. Ich weiß nicht.

TFSR: Wie waren die Einrichtungen im Ag Center?

Chris: Es gibt dort ein großes Gebäude im Agrarzentrum, das für alle Kinderbetten und alle Unterkünfte genutzt wurde. In diesem Gebäude gibt es eine kleine Küche. Es ist ein großes, offenes, hohes Gebäude, eine Art kleine Arena, aber flach. Als ich dort war, herrschten keine besonders guten Bedingungen, da es weder Strom noch Wasser gab. Sie hatten ein paar kleine Generatoren, um zumindest die Sauerstoffgeräte einiger Leute mit Strom zu versorgen, was ein anhaltendes Problem darstellt. Alle Menschen, die Sauerstoff benötigen; Die Leute haben vielleicht Flaschen, aber sie halten nicht besonders lange. Irgendwann war ich tatsächlich dort, als sie einen Generator hatten, den sie eine Zeit lang nutzen konnten, der aber irgendwo in der Nähe einer Vermietungsfirma gehörte, und sie kamen tatsächlich und nahmen ihn zurück.

TFSR: Ihr habt es mitten in der Hurrikanhilfe zurückerobert?

Chris: Sie haben es vor allen Leuten zurückgebracht, vor Hunderten von Leuten. Es handelt sich um eine private Vermietungsfirma. Wofür glauben Sie, dass sie es verwenden werden? Um Geld zu verdienen! Ich gehe davon aus. Ich weiß es nicht genau, aber ich denke, es ist eine gute Wahl. Das war’s also. Nach einer Weile fand ich endlich ein paar andere kleine Generatoren. Nun gibt es dort Ressourcen auf nationaler Ebene, die in Bezug auf die Ressourcen viel besser aufgestellt sind. Auch die Polizei ist dort deutlich verstärkt. Ich kann mir nur vorstellen, dass viele Leute einfach gehen wollten, sobald das Wetter nachgelassen hat und die Dinge viel reglementierter sind, wie es bei der Ankunft der FEMA der Fall ist. Es gibt viele Leute, mit denen ich oft zusammenarbeite, die bereits auf der Straße leben. Sie sind in vielerlei Hinsicht sehr überlebensfähig und haben den unmittelbaren Sturm überstanden. Ich werde sehen, wer morgen draußen ist, wenn ich wieder zur Arbeit gehe. Es fließen definitiv Ressourcen. Es werden viele Dinge vorbereitet.

Ich war in letzter Zeit nicht im Ag Center, aber es gibt ein paar Notunterkünfte im örtlichen Community College. Dort wurde die medizinische Notunterkunft eingerichtet. Auch dort war es schwierig, die ersten paar Tage zu überstehen. Es ist eine gute Idee, eine solche Unterkunft zu schaffen. Allerdings brauchen viele Leute dort Sauerstoffgeräte, und es gibt zwei winzige Generatoren. Großartig, aber sie brauchen Benzin. Es ist also ein Kampf. Menschen brauchen Wasser. Eine Gruppe kam und warf diese süßen Port-A-John-Anhänger weg. Sie sind bereit zu gehen. Aber es gab ungefähr fünf Schritte, um zu jedem einzelnen von ihnen zu gelangen. Sie befinden sich auf einem Anhänger, sodass fast niemand in der medizinischen Unterkunft sie benutzen konnte. Glücklicherweise gab es einen Port-A-John, der ebenerdig war. Das war also eine weitere Sache, die ausgetauscht werden musste. Wir mussten die Lücke des unmittelbaren, schwersten Teils überwinden. Ich habe alle Namen der Phasen vergessen, aber es gibt Phasen der Katastrophe. Die unmittelbare Akutsituation, wenn Rettungsaktionen stattfinden und Menschen um ihr Leben kämpfen müssen. Dann kommt der nächste Teil, in dem der Schaden noch frisch ist und immer noch Menschen gerettet werden müssen. Die meisten Menschen suchen Schutz, Wasser und das Nötigste. Also helfen wir einer Reihe von Menschen, diese zweite Phase zu überstehen, und jetzt fließen viele Ressourcen in beide. Eigentlich gibt es drei Streams. Es gibt staatliche/offizielle Organisationen, es gibt gemeinnützige Organisationen und es gibt Basisorganisationen.

TFSR: Dies ist der letzte Funke, der das Fass zum Überlaufen bringt, und Ihr habt gerade unser Gespräch mit Chris gehört, einem Rettungssanitäter, der im Westen von North Carolina Pflege leistet.

Ich weiß, dass ich es in vielen Fällen vermeide, Spenden zu leisten oder Spenden für NGOs oder gemeinnützige Organisationen wie offizielle Gruppen zu fördern, weil viel Geld von Organisationen wie dem Roten Kreuz in die Finanzierung von Verwaltungspositionen oder Lobbying-Bemühungen fließen kann , oder andere Dinge, und nicht tatsächlich zu den Menschen gelangen, die die Vorräte oder Ressourcen vor Ort direkt benötigen. Das soll nicht heißen, dass sie einige Dinge nicht sehr gut machen, aber gibt es vor Ort gute Organisationen, an die die Leute spenden könnten? Was sind gute Methoden, um festzustellen, ob eine Gruppe vertrauenswürdig ist? Jemand erwähnte zum Beispiel eine Gruppe namens Appalachian Medical Solidarity, die Spenden sammelt, und jemand, der sich ihre Geschichte anschaute, meinte: „Nun, sie haben in den sozialen Medien in den letzten fünf Jahren kein großes Muster gezeigt.“ Sie waren hin und wieder da.“

Chris: Ich habe die Erfahrung gemacht, dass einige Gruppen in den sozialen Medien gut sind. Ich wurde eigentlich nur an diese Gruppe erinnert? Sagen Sie mir, wenn ich falsch liege, aber war es Queer Appalachia?

TFSR: Ja.

Chris: Sie hatten eine wirklich tolle, nette Social-Media-Präsenz, hatten tolle Merchandise-Artikel und sammelten angeblich viel Geld für gute Zwecke. Die Leute können die Artikel darüber nachschlagen, wie das gelaufen ist.

TFSR: Es gibt einen großen Artikel in der New York Times darüber, der sehr ins Detail geht.

Chris: Es stimmt, dass sich die sozialen Medien ziemlich schnell verändern. Selbst Plattformen ändern sich ziemlich schnell. Die Leute betrachten also verschiedene Dinge. In diesem Sinne ist es gut, für eine Gruppe eine gewisse Medienpräsenz zu haben. Das hängt mit etwas zusammen, an das ich erinnert wurde, als Sie das Rote Kreuz und all die Verwaltungskosten erwähnten, die meiner Meinung nach übertrieben sind. Das Rote Kreuz ist so groß, dass es in vielerlei Hinsicht ein Arm der Regierung und des Staates ist. Sie sind jedoch von Dauer. Sie sind bereit. Sie halten zwischen den Ereignissen an, das ist es, worauf ich hinaus will. Es scheint schwierig zu sein, weil ich an verschiedenen beteiligt war, bei denen nicht viel im Sinne von Dringlichkeit, Krise und Straßenaktionen passiert, um die Infrastruktur aufrechtzuerhalten und vielleicht nicht aufzubauen, aber zumindest die Strukturen der Gruppierung aufrechtzuerhalten, physische Speicher, Fundraising, all das Zeug. Ich verstehe, dass AMS derzeit viele Mittel erhält. So sehr, dass ich denke, dass es den Leuten gut tut, sich andere Orte zu suchen, denn wenn viel Geld in einen Kanal fließt, kann es zu einem Engpass, auch zu einem technologischen Problem oder einfach nur zu Kapazitätsproblemen kommen.

Ich kann sagen, wen ich empfehlen würde. Ich weiß, dass Mutual Aid Disaster Relief eine Erfolgsbilanz bei der Wartung einiger ihrer Systeme und der Mittelbeschaffung vorweisen kann. Sie sind eine offizielle gemeinnützige Organisation mit sehr engen Beziehungen zur Basis. Soweit ich weiß, handelt es sich im Wesentlichen um eine Basisorganisation, die eine offizielle gemeinnützige Organisation ist und über Integrität verfügt. Ich habe an verschiedenen Orten und in verschiedenen Fällen mit ihnen zusammengearbeitet. Daher würde ich sie weiterempfehlen. Und es gibt noch einige andere lokale Orte.

TFSR: Rural Organizing and Resilience ist eines, das wir bereits in der Sendung interviewt haben. Ich weiß nicht, wie ihre Online-Präsenz aussieht, aber ROAR leistet gute Arbeit.

Chris: Richtig. Sie haben eine einfache Website und ein Facebook. Sie haben definitiv eine Spendensammelstelle, an die Leute Geld schicken können. Ich weiß, dass ich Kontakt zu ihnen hatte. Sie rocken besonders im Madison County und einigen anderen ländlichen Gegenden in der Nähe von Asheville. Ich weiß nicht, wie sie in den Medien präsent sind, aber sie haben einige Spendenkanäle. Ich weiß direkt, dass die Leute auch Vorräte eingebracht haben, das Geld ausgegeben haben, die Vorräte besorgt haben und sie zurück in die Gegend gebracht haben.

TFSR: Wenn wir über Katastrophen und den Zugang zu Ressourcen im Sinne von Marginalisierung nachdenken – sei es geografisch, kulturell, wirtschaftlich oder was auch immer –, sind viele der vom Sturm am stärksten betroffenen Menschen vielleicht die Menschen, die bereits vorher in marginalisierten Positionen lebten. Was cool ist, dass Sumud Dinge tut, oder zumindest die Mitglieder Dinge tun. Ein weiterer Aspekt, den wir bereits bei ROAR erwähnt haben, ist, dass sie in ländlichen Gebieten arbeiten, die oft von Ressourcen abgeschnitten sind und wo eine kleine Änderung der Infrastruktur jemanden wirklich vom Zugang zu Frischwasser, Strom, Wärme, Medizin usw. abschneiden.

Chris: Es ist wirklich wichtig, dass sich die Leute daran erinnern, dass wir alle blinde Flecken haben. Wenn ich also in eine Gegend komme, ist es meiner Meinung nach ein guter Grundsatz, eingeladen zu werden und nicht unbedingt aufzutauchen. Ich verstehe, wenn man nicht weiß, mit wem man reden soll, aber es sind bereits Leute vor Ort und das macht mir sehr Mut. Ich habe das noch nie erlebt, direkt dort, wo ich wohne. Ich war bei mehreren Katastrophen dabei, mich einzumischen.

Seit Freitag ist schon einiges los. Ich bin gerade in die Stadt gefahren und habe auf der Fahrt mindestens ein halbes Dutzend Verteilungsstellen an verschiedenen Orten gesehen, beispielsweise in einer Grundschule, bei der Feuerwehr und in einigen Kirchen. Und Restaurants, die Essen anbieten, kochen es einfach und verschenken es. Niemand wandte sich ab. Ich denke, durch die Corona-Erfahrung und andere Erfahrungen haben viele Menschen sozusagen ihre Solidaritätsmuskeln aufgebaut und sind bereit, sich der vor ihnen liegenden Herausforderung zu stellen und nicht darauf zu warten, dass der Staat oder die großen gemeinnützigen Organisationen starten. Natürlich verlassen sich die meisten hier auf die Wiederbelebung der Industriegesellschaft – all der großen Systeme, der hierarchischen Systeme –, um es noch einmal klar zu sagen. Ich denke jedoch, dass es Fortschritte gibt. Zumindest habe ich das Gefühl, dass es so ist, in meiner direkten Erfahrung. Als würde man an Menschen denken, die im Kapitalismus und unter verschiedenen Unterdrückungssystemen jeden Tag mehr am Rande leben. Es gibt so viel zu lernen. Wenn jemand bei der Arbeit etwas Wissen mit mir teilt, hilft das auch meinem eigenen Überleben. Ich bin so dankbar und habe immer das Gefühl, dass wir in einer gemeinsamen Sache stecken. Das sage ich den Leuten laut. Ich habe nicht das Gefühl, dass es eine Fälschung ist. Wir sind hier. Ich stehe hier neben dir. Ich weiß, dass dies ein langer Notfall ist, eine Katastrophe (ich glaube, es ist der Titel eines Buches, eigentlich „Ein langer Notfall“), aber wo wir hingehen, wo die Zukunft jetzt ist, passieren die Katastrophen überall.

Der Kapitalismus und die großen Systeme werden immer weniger effektiv darin, das bereitzustellen, was wir tatsächlich brauchen. Dieses Krankenhaus hier wurde von der größten Krankenhausgesellschaft des Landes aufgekauft, und sie sind so riesig und reich, und der Service wurde so viel schlechter. Jeder hat es gesehen. Jeder sieht es. An zufälligen Dienstagen kam es zu einer Art Mini-Katastrophe. Rettungsdienste, Arbeiter, Rettungsdienste und Krankenwagen mussten ihre Patienten mehr als zwei Stunden lang auf ihren Tragen warten lassen, einfach an einem normalen Tag vor der Tür auf den Parkplatz hinausgehen, weil das Krankenhaus verdammt billig ist, und sie wollten die Gewerkschaft brechen. Sie wollen die Gewerkschaft, die gerade erst gegründet wurde, durch Unterbesetzung, Billigung und all diese Dinge immer noch zerschlagen. Ich möchte hier nicht auf die falsche Fährte gehen, aber das ist ein Beispiel für Dinge, denen wir uns stellen müssen. Ja, das ist scheiße, und es ist auch eine Gelegenheit, etwas über Menschen zu lernen, die Nachbarn sind, neue Leute kennenzulernen, zusammenzuarbeiten, Wege zu finden, damit umzugehen, sich an diese Dinge zu erinnern und einige Beziehungen aufrechtzuerhalten. Ja, auf lange Sicht, oder?

TFSR: Ich erinnere mich, dass es in der Wirtschaftskrise von 2008, die der Kapitalismus verursachte, zu einem großen Zustrom von Menschen kam, die auf der Straße lebten, weil ihnen ihre Wohnungen weggenommen wurden. Ähnlich verhält es sich nach der Corona-Krise mit der gegenseitigen Hilfsarbeit in Asheville, wo, wie an vielen anderen Orten auch, das Narrativ lautet, dass Menschen von außerhalb der Stadt hierher gebracht werden, nicht hierher gehören und weiterleben in Straßen und unserer Ressourcen. Für Menschen, deren Wohnverhältnisse prekär sind oder die auf der Straße leben: Jedes Mal, wenn es eine Krise gibt, werden Menschen aus ihren Unterkünften gedrängt. Oft fehlen ihnen die Mittel, um in eine andere Stadt zu ziehen, und so leben die meisten Obdachlosen in Asheville schon lange in Asheville. Angesichts all der Schäden, die der Sturm angerichtet hat – weggeschwemmte Häuser, unterspülte Straßen, Überschwemmungsschäden und Schlamm überall – welche Auswirkungen wird sich das Ihrer Meinung nach auf die obdachlose Bevölkerung in Asheville auswirken?

Chris: Nun, ich denke, die Leute können auf New Orleans zurückblicken, um dort einige klare Lehren zu ziehen. Ich denke an einen Mann, den ich bei meiner Arbeit gesehen und getroffen habe. Er hatte gerade erst vor einer Woche eine Wohnung bekommen, und ein großer Eselbaum ging gerade durch sein Haus, während er darin war. Er hat mir die Geschichte erzählt und jetzt ist er wieder auf der Straße. Wird es so sein? Was wird mit diesem Haus passieren? Es wird wahrscheinlich repariert werden, aber der Aufwand und das Geld, um es zu reparieren … wer weiß, wie lange das dauern wird? Je nachdem, wem es tatsächlich gehört, was würden sie damit machen? Werden sie es in einem Programm behalten, in dem Menschen eine Unterkunft finden können? Gute Frage. Auch in einigen dieser ländlichen Gegenden gibt es große Schäden. Außerhalb von Asheville wird es ziemlich schnell ländlich und es ist schwer zu sagen, wie die Zukunft dieser Häuser, dieser Gebiete, dieser Viertel aussehen wird. Nach dem, was ich in der Vergangenheit gesehen habe, werden die Menschen genau an der Stelle wieder aufbauen, an der alles zerstört wurde, wie zum Beispiel im Lower Ninth Ward. Was wird es zur Gentrifizierung beitragen? Ich weiß nicht.

Katastrophen treten in immer schneller auftretenden Häufigkeiten und Schweregraden auf. Es gibt einen Punkt, an dem es Dinge wie die Gentrifizierung ausgleicht. Irgendwann wird es wirklich schwer. Ich denke hier an die Wohnprojekte. Ich habe buchstäblich den CEO einer großen Seniorengemeinschaft getroffen, die auch einige Gebäude für betreutes Wohnen hat. Ich bin mir ziemlich sicher, dass es dort tatsächlich eine qualifizierte Pflegeeinrichtung gibt. Es ist ein großer Ort, wirklich schön, hochwertig, und der CEO kam vorbei, um herauszufinden, wie er sicherstellen kann, dass seine Leute versorgt werden. Wo ist andererseits der Sozialwohnungsbau? Ich weiß nicht alles, was vor sich geht. Ich weiß nicht unbedingt, was der CEO der Wohnungsbehörde hier tut. Ich weiß, dass es stimmt, dass die Menschen in diesen Projekten nicht den gleichen Service erhalten. Wer setzt sich dafür ein, dass sie das bekommen? Die Babys, ältere Menschen, Familien mit sehr kleinen Kindern, sogar Kleinkinder. Wir brauchen die Windeln, die Säuglingsnahrung, die Vorräte. Ich weiß, dass die Leute an der Basis diese jetzt liefern, also haben wir das verstanden.

TFSR: Ja, wie Du sagst, blinde Flecken. Das Beste, was wir tun können, ist zu versuchen, sie zu reduzieren und voranzukommen. Nun, Chris, vielen Dank für dieses Gespräch. Gibt es noch andere Dinge, die Du einbringen möchtest? Ich habe Dich länger behalten, als ich versprochen hatte.

Chris: Ich schätze es, dass sich Leute engagieren. Wie ich schon sagte, wir müssen uns selbst überprüfen. Wir überprüfen unseren Retterkomplex. Es gibt keine Helden – das ist eigentlich nur ein Manipulationsmechanismus. Da wir beim Militär und in anderen Berufen gearbeitet haben, in denen wir Helden genannt werden, geht es nur darum, uns davon zu überzeugen, uns selbst zu opfern. Das ist etwas, das uns trennt. Wir müssen Barrieren überwinden, seien es soziale oder institutionelle, damit wir alle überleben und gedeihen können. Deshalb schätze ich es, wenn sich die Leute darauf vorbereiten. Das ist mein letzter Gedanke. Lasst uns nicht nur Adrenalinjunkies sein, okay? Lasst es uns aufbauen und zumindest auf einem Plateau halten, damit wir nicht viel davon neu aufbauen müssen, wenn die Scheiße wieder auf Hochtouren läuft.

. … . ..

Margaret Killjoy Transcript

Margaret Killjoy: My name is Margaret Killjoy. I use she and they pronouns. While I am currently recording this from West Virginia, I spent two days down in Asheville, North Carolina. I was on a book tour when all this happened, and I have a lot of prepper stuff, because that’s one of the things that I do. I was connected in with Mutual Aid Disaster Relief to a certain degree, and I have large van. I drove a lot of equipment down, was there for two days, and just got home about an hour ago.

TFSR: And Renshaw was there.

MK: That’s true. My dog, Renshaw was there.

TFSR: When you say “all this happened”, could you just give a real quick rundown about what just happened?

MK: Yeah, one of the things that’s wild is how few people know what’s happening. I was in Blacksburg, Virginia, which is not very far away from Asheville, North Carolina, and is in a very similar bio region. Of the two people I talked to while I was buying supplies, one person had no idea what was happening there, and the other was like, “Yeah, that’s because no one pays attention to things in Appalachia. Everyone abandons us.” Asheville, North Carolina and the surrounding areas managed to be in sort of a perfect storm. It wasn’t just the hurricane. This part is a little bit rumor, as in, this is a part that comes from talking to someone on the ground.

TFSR: Are you going to talk about HAARP?

MK: Oh, not that stuff yet. No. Rather, it’s simply the weather pattern that caused this. According to a friend I talked to, on the ground, there were eight inches of rain before the hurricane hit, the day before the hurricane hit. Imagine a zipper of two storms coming together. Appalachia has been in a severe drought all summer. Then eight inches of rain. For people don’t normally keep track of how much an inch of rain is, an inch of rain is a lot. If it rains an inch in a day, that’s an awful lot of water. It got eight inches of rain before the hurricane hit. So if you see the areas most affected by the hurricane, and it’s kind of curious about this area inland, getting it worst. It’s just sort of a terrible perfect storm. Asheville, North Carolina and the surrounding areas (and those often get forgotten but there’s a long list of them.) Western North Carolina and parts of Tennessee were hit with very severe flooding. A lot of people think that mountains don’t flood. Those people have not lived in mountains. They simply flood in a very different way than flatlands flood. Mountains, because of the hollers, which is the area between the hills, when they flood, the water runs down and is channeled into these places. So you actually get this very strong flooding, but it’s a little bit more of a network of floods, rather than like the entire area underwater. Unfortunately, those areas are also where we put our roads, and are also often where people build their homes.

TFSR: So this is millions of people throughout the region that have been left without electricity, without cellular connections, without water supplies, effectively. In a lot of cases, because of those geographic disconnections of the hollers or the branches, isolated from each other. So stepping to a different question from here, and we’ll get back to this: You’ve been living in different parts of Appalachia for a number of years, so you’ve had experiences with the way the terrain is structured, and the way weather falls and such. You also do a lot of thinking on emergency preparedness. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about Live Like the World is Dying, and the concept of community preparedness that you work through there.

MK: I’m one of the hosts of a podcast called Live Like the World is Dying. It’s a community and individual preparedness podcast that I started because I was getting into being a prepper. I actually started probably about 2016, collecting beans and rice and things like that, because of some conversations I was having with a food land use engineer friend of mine about the possibility of food shortages in 2020. I finally decided, I’m just gonna go ahead and make a podcast about this. This was January 2020 so the first couple episodes were like, “I’m doing a prepper podcast”, then immediately covid hit, and prepping became more popular, unfortunately. Well, I mean, fortunate that prepping became more popular, unfortunate why it had to. The core idea of Live Like the World is Dying, or at least my approach to preparedness, is that we’re often presented with this dichotomy between individual and community. Everything- preparedness included, but also just life, the entire 20th century- lives in the shadow of the Cold War, where you have this authoritarian, pro-communal system, and then you have this pro-individual capitalist system. These get presented as these opposites. You have to either pick the community or the individual. I, and I would say universally, anarchists reject this dichotomy. One of the ways that applies is in disaster preparedness.

Most preppers talk about individual preparedness. When I’m making fun of that, I call that the bunker mentality, or the “I’ve got mine. ^%$# you” mentality. Which is the problem we’re facing at the border right now. I think the right wing is aware of the climate crisis and just doesn’t want to admit it and that’s part of why they’re like battening up the hatches. They understand that bad things are coming and are here. I have no interest in the bunker mentality. Yet, at the same time, the way that some people talk about community preparedness, is only about community resources and networks and hubs and things like that. Those are absolutely essential but I believe that individual preparedness is a very useful part of community preparedness, and I have never felt more certain of it than I have in the past few days. One of the reasons I was able to show up in Asheville is that you don’t normally want to respond and self-deploy to disaster situations. When you do, (I didn’t self-deploy. I collectively deployed, came down with a small caravan of people and connected in with some people ahead of time) you have to be prepared to be individually self-reliant. So I made sure that I had at least one week (I think I ended up with two weeks) worth of food and water and other basic necessities available to myself. I went down in a van that I can sleep in. I, as part of the caravan, made sure that we had extra gas. I also was very aware of the gas in my car. I basically did everything I could to make sure that I would not become, in any way, a drain on resources and the more prepared someone who is living in the crisis zone is, the better prepared they are to help other people. You could see it right away on the ground. Most of the time in a disaster situation, your first priority (and this isn’t selfish) is making sure that you have your needs met and that the people around you have their needs met. Once you’ve done that, you can start thinking bigger. Now a lot of having your own needs met involves coordinating with people around you but a lot of the people who were first out providing things, were the people who were saying things like, “Well, I was okay” because if your house wasn’t washed away, (which happened to a lot of people, but not most people) your problem is that you have no food, you have no communication, and you have no water. So people who have those things available because they’re prepared, were immediately out helping people. I basically, just cut my prepper stash in half and brought it down. I talked with people who are more prepared inside Asheville who were like, “Yeah, I kind of just did the same thing.” About half of my freeze dried food went out immediately.

I hate the dichotomy between individual community preparedness and I’ve never been more convinced that it’s a false dichotomy. I’ve never been more convinced. People have asked me, “how do you support what’s happening?” I know I’m running on a tangent, but it’ll be worth it. People have asked me a lot, “how do I support this?” If you’re far away- usually the answer isn’t drive in there. If you are connected in with groups, including self-organized groups and you can be self reliant or reliant with the people that you’re going in there with, maybe going in is useful. Maybe. If you’re within a day’s drive, coordinating to get supplies there is necessary. People have been setting up hubs all over the Southeast and the Mid-Atlantic. Coming from further away than that, people are setting up places for people to drop off supplies, and then drivers are then taking them into Asheville. Inside Asheville, drivers there are taking them out to the surrounding areas. If you’re about a day’s drive away, do that. If you’re further away than that, you can donate. You can donate to a Mutual Aid Disaster Relief. You can donate to Appalachian Medical Solidarity. I’m sure there’s a whole list of folks that you’ll be shouting out. If you don’t have enough money to donate, or you’ve kind of donated what you can, (these days, we all need money all the time) I would say the main way that you can help, is to start taking preparedness seriously as an individual and a household, so that you’re in a better position to take it seriously as a community during crises. Asheville was (there’s some newspaper I can’t remember, that picked it as) the number one climate haven in the United States a couple years ago. What does that mean? There is no haven on planet earth from the warming planet earth.

TFSR: When Occupy was happening, Rosetta, from Rosetta’s Kitchen, was doing a bunch of research into food deserts and looking at how destabilized the area was whenever there was a cut off of distribution of food. There’s not food produced at any scale in that part of Appalachia. The grocery stores only hold food for like three to five days for the amount of people that are there. We’ve heard that stores like Ingles were actually locked down at a certain point and not selling what was on the shelves for whatever reason, because they were afraid of looting or whatever. There is a food bank in the area, but all that stuff would dry up pretty quickly.

I’ve seen when there’s been a breakdown of gasoline for instance and that’s messed up trucking. A couple years ago on the Colonial Pipeline, when those cyber attacks were happening, our area was out of gas pretty quickly within a few days, and there were huge lines around the corner for all sorts of people.

MK:I talked to person after person (because I also went there as a journalist, although that was sort of the afterthought, slash, the way to justify it to work.) I asked everyone about their own preps and what did and didn’t work, and what they wish they had done. Everyone gets kind of lazy about stuff here and there. I talked to a friend who had a lot of stuff prepared at home. She was like, “Well, I only had an eighth of a tank of gas when I got home the night before, and I didn’t bother getting more, even though I sort of knew a storm was coming. That’s not because that person messed up. That’s just what all of us do. There are things that we just have to make habits. I was just thinking about those gas shortages.

TFSR: So there were two kinds of preparedness that you were talking about- the individual preparedness, and the community preparedness mindset. They’re not fully disconnected from each other, as you pointed out. I wonder about what you witnessed, because there has been a governmental response. FEMA, National Guard have been showing up in Boone, and Border Patrol has been showing up. I’m sure a number of other agencies have been appearing on the ground. Some of them, like FEMA, set up the shelters at the Ag Center across from the airport in Asheville. I’m sure they has been facilitating distribution points for water and food variously. There’s also the other element of the way that the government interacts with crises like in the name of FEMA. It’s it’s the management of an emergency. Did you see or hear anything about people being stopped from bringing in aid or blocking people’s access to certain areas, blocking people from returning home? Any of that sort of stuff, or the centralizing of distribution hubs so as to be able to manage that would maybe leave more decentralized communities behind?

MK: First of all, my bias is that I want to find things that the government is doing badly and talk about them. That said, I have attempted to follow up on every rumor that I have found, of these things while I was there, and I did not successfully follow up on a single rumor about people being blocked from providing aid. The closest that I found was some of the people driving into some of the more remote or the smaller towns, a sheriff stopping people saying, no, no one can come in. And the people were like, “Oh, our car’s full of diapers” or whatever it was, and the sheriff was like, “Oh, you can come in.” I’m also aware there was a highly publicized news story that’s outrageous, about a helicopter pilot who self-deployed to go rescue a bunch of people and then was threatened with arrest. I’ve also talked, and this is also kind of on the rumor level because I didn’t talk to the pilots, I also heard about other sheriffs, or local police in different areas, when helicopter pilots were like, “Hey, I’m going to go try and rescue people.” They were like, “Great, we’ll shut down the airspace for you.” You know, “we will make this happen.” So it seems like there’s a lot of confusion about what federal disaster relief looks like and there’s a difference between, for example, disaster response and disaster relief. I passed a lot of, I forget the name of the agency, but it was a different agency that wasn’t FEMA. I passed a lot of their vehicles on the road on my way in. It was the Federal Disaster Response, something. I don’t know. I was like, “hmm, that’s not FEMA. How many things do they have like FEMA?” More and more, I’ve been learning FEMA is an insurance company. FEMA shows up to finance things. One of the things that came up is that FEMA is aware that volunteers do most of the work in this kind of situation, and that the organic structure, in some ways, it’s almost like the government not doing some of the hard work and getting us to do it instead.

For the people who are there for response versus relief: Response is the immediate thing. A lot of the people who are looking for these shorter deployments tend to be military types, law enforcement types. These people have a problem when they see structurelessness. They’re like, “our goal is to impose structure upon this,” and that’s a problem. It is a problem because certain circumstances, I would argue in most circumstances, do better with an organic and dynamic structure, rather than a rigid and hierarchical structure. However, the kinds of people who show up immediately from the government, often tend to be more of the enforcement type. This is the best way that I had it explained to me. That said, there have been so many rumors about so many things. There are rumors about road blockades, for example. I would be getting these texts about road blockades into Asheville, and they would be describing roads that I had just driven on. Then I was like, “Oh, they must have set it up afterwards.” Someone showed up 10 minutes later, and was like, “No, I just just drove on them too.” I might be eating my hat in a week…it’s possible that these things are more of a problem than we expect, but I actually think one of the things that disasters do, is get us to drop some allegiances. Our allegiance becomes humanity, and that includes those of us who claim that our allegiance is humanity this whole time. Don’t get me wrong. There are people who show up and try and enforce structure. Katrina was a really good example of this. There’s always government or militia types showing up and deciding that law enforcement is the single most important thing. Those people are dangerous in multiple ways, but I think we can exaggerate them and accidentally create a sort of a tension between formal and informal disaster response that doesn’t always need to be present. When I talk to disaster response people, I often get the sense. I know of anarchists who boss around National Guardsmen on a regular basis because of disaster relief work. Call me a liberal for this. I don’t care.

TFSR: Little bits and pieces of information are coming out. There’s a couple of chemical, plastic plants in that region of southern Appalachia, that have been affected by the storm. There’s the story in eastern Tennessee of the plastics manufacturing factory, where six workers died because the floods came through and their bosses wouldn’t let them go home. Then there’s the fabrication spot in Woodfin, which is just north of Asheville. The French Broad, which is the main river that goes through Asheville. It actually flows north, so downriver, but North of Asheville, a bunch of solvents appeared to have been released into the water with some of the flood. People are reporting rashes and burning of their eyes and their nose from inhaling dust and starting to feel the effects of it. Obviously, you’re not a chemist, you’re not a doctor but I wonder, as someone who just came back from there, if you’ve heard similar things to that.

MK: Most of those rumors (which I give a lot more credence to than some of the other rumors that I was just saying, that I might be wrong about) I don’t specifically trust…most of these rumors started today as we record this, which was the day that I was driving away from Asheville. However, you know that said, every disaster does this, and so I have every reason to believe this. That’s part of the man made part of natural disasters. Not just that we do all of this heavy industrial work, which people have complicated feelings about, I have complicated feelings about. But the fact that, because they’re private industry, and because they’re beholden to stockholders and capital, they don’t prioritize not having negative impacts on the environment in case of crisis and storm. I was talking to someone about (sort of tangential, but) a place that sells really nice outdoor gear. They didn’t empty it before the storm, even though they were right on the river. The place is just totally destroyed. Basically, people are sitting around being like, “Oh, where are we going to get a bunch of water filters?” And someone’s like, “well, I know there’s a bunch of water filters, but we can’t have them. They’re under water and they’re under poop water.” Never use a water filter that’s just been submerged in a flood forever.

TFSR: Well, I was hearing a few days ago about people having rashes in Madison County, and it was explainable because of kerosene and other chemicals in the water. You mentioned being prepared and thinking about what needs could arise before. Preparedness is about being ready, not necessarily knowing what is it going to occur, but at least having some sort of small response. Having a gas mask, having an extra chainsaw around, that’s sharpened and ready, is something. Having a few gallons of water set aside, is better than not having that. One downside of the response of large agencies like FEMA or the Red Cross, or other agencies showing up, is that while they have they have the resources, which is amazing, and they have the science of deploying them in certain centralized ways- preparation for disasters based on community networking and relationships with your neighbors, seems like a really important thing. Especially if you don’t have the ability to go down to the Ag Center, you don’t have the ability to get down to the Ingles where someone is deployed and handing out food. Is talking to your neighbors a thing that you really want to talk about right now?

MK: Yeah and I know I just kind of defended the federal response, and I don’t really mean to. More just, I want to, say that we’re not certain about certain things they’ve been accused of, because I want to be accurate when I discuss them. There are fundamental problems with this sort of centralized and bureaucratic method. We’ve been learning that even the Department of Homeland Security put out a paper in 2012 saying Occupy Sandy was more effective than them. Basically, because the decentralized network was able to fill in gaps. But it’s more than filling in gaps.

TFSR: It was agile.

MK: Yeah, exactly. It’s something that I run across all the time. I used to work in cooperative economics. During the beginning of the pandemic, worker cooperatives survived the shutdowns substantially better than traditional businesses, despite the fact that people claiming that traditional capitalism is somehow better at economics. Cooperative businesses did better because they were agile, because they were able to respond in different ways, because they could have different priorities. There are certain things that you sort of need the big thing to do, but there’s no reason we can’t be doing the big thing. Just before this call, I was talking to someone from a large, international NGO, who said, “Hey, how do I get some supplies that are supposed to go to our site, to these sites that are decentralizing it out better?” People want to do that, because, at the end of the day, people’s allegiance is to humanity. Or people forget that, and their allegiance is to bureaucracy and control, in which case they get in the way of people trying to get ^#@ done. But small crews with chainsaws get stuff done, and many hands make light work.

In terms of talking to our neighbors.. this morning, I woke up to the 70 year old or so couple who lived behind my friends house coming over and thanking us for the water that we dropped off at their house the day before. Then they brought us news about what was happening in a different town, and being blurry about all of it on purpose. “Oh, we went to go see our son who works in this different town, who works for the such and such city department and here’s what they know.” We’re all sitting there talking, and they don’t care that we all have weird names and are dressed funny because at some level you’re just like, “Well, do you need D batteries for your radio? I have them.”

My other favorite moment of the whole thing was, I was sitting outside my friend’s house, and this guy drove up, and he got out of his car and was like, “Water?” And we were like, “Uh, what?” and he’s like, “Do you have water?” And he wouldn’t come near us. We were five subcultural people wearing black, sitting around in the front yard and he was not subcultural, driving a nice car. I understand why he wasn’t immediately like, “I’m just gonna come up and talk to you.” But he lived nearby, and these people hadn’t met him before. He lived in know, one of the sort of fancy new houses on the street. After he found out we had water, he asked about each individual house near us and made sure that all of those people had water and wouldn’t leave until they did. The thing I loved about that interaction, at no point did I get the impression he liked us, and that didn’t matter. Whereas the other interaction with the neighbors were friendly. There’s some subcultural barriers that have broken and generational barriers that have broken, and maybe class barriers, but I don’t know. That’s not always gonna happen. Sometimes you’re gonna be like, “Oh, we still don’t want to hang out. You got what you need? Do you need anything? I’ll get it for you.” So in some ways, a lot of the stuff that people worry about with preparedness, those problems sometimes melt away after disaster. That’s not to say we shouldn’t be prepared. We should be prepared. For example, the “knowing your neighbors” stuff- if it’s hard to talk to them when it’s not a crisis, it might be easier to talk to them when there is crisis. Because you know why you’re talking to them, and they know why you’re talking to them. So a lot of .. flooding is a good social lubricant! [laughs]

TFSR: [laughs] Okay. Okay Margaret. That’s lovely. Thank you. I think that’s a good place to end. You already addressed the climate concerns. I think that listeners should really go and listen to Live Like the World is Dying. I think it’s a really great podcast. It’s a member of the Channel Zero Network, and I wish that there was a promo jingle that I could play.

MK: I know, if only there was a jingle. How is anyone to know that they’re part of Channel Zero Network? For anyone who’s wondering why we don’t have a jingle and we’re never on it- it’s a too many cooks problem. We’ve always sat down and been like, “oh, all of us hosts should be on the jingle,” and then getting all of us into the same Zoom room at the same time keeps not happening. Now we’ve just challenged each other that someone should just do it. And then we haven’t done it, but we have a podcast called Live Like the World is Dying on the Channel Zero Network.

TFSR: Thanks for going to Asheville, and thanks for being networked in and being a comrade and for all the work that you do. It’s really appreciated.

MK: Thank you.

TFSR: Yeah, of course. And I hope that you get some really good sleep. It’s well earned.

MK:Thanks. I I hope so too. And thanks for also doing all this. And I’m so sorry if you’re having disaster FOMO.

TFSR: I absolutely am, so I just interview about it like a podcaster.

MK: That makes sense.

. … . ..

Margaret Transcript auf Deutsch